Tips · 8 MIN READ · PETER MICHALSKI · MAR 6, 2019 · TAGS: Cloud security / Get technical / How to / SOC / Tools

Many of our customers run at least part of their infrastructure in public cloud environments, like Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud or Microsoft Azure. And while there are plenty of benefits of using the cloud, there are also unique security concerns that organizations need to be aware of. In short, that same security playbook you were using to chase down alerts on your network, laptops and servers isn’t always going to work once you’ve lifted that data into the cloud.

Why? We’ve talked about a few reasons here, but the TL;DR is that your users are the new endpoints.

One of the biggest challenges we see with cloud security is that people are unpredictable and prone to, well … ya know, being human. So we often see security incidents happen that are simply errors made by well-intending employees. While they mean well, these errors can (and do) inadvertently put their organization at risk.

One of the most common errors that’s been popping up in the news and which we’ve started to see here at Expel is when users accidentally make Amazon S3 buckets public.

What’s Amazon S3, why do these breaches happen and how can you protect your own org from making this mistake? We’re laying out all the details for you below.

What is Amazon S3?

Amazon S3 (“S3” stands for “Simple Storage Service,” BTW) buckets are basically the equivalent of hard drives in the sky. They can be used to store images, videos, websites, backups, new application builds or really anything you want. You can even host a website using Amazon S3, and store all the elements on said website in a bucket.

When you create a new Amazon S3 bucket, you’ve got to set a bunch of configurations and settings. You can also adjust the access permissions policies for the bucket and all the data contained in it (more info on all of that right here). S3 buckets don’t allow public access by default, so if a bucket becomes public, it means a user made a change somewhere along the way.

The potential for exposing data through public S3 buckets will always be a risk (even if it’s unintended), but there are a couple steps you can take to quickly identify public-facing S3 buckets and reduce your risk of an incident. Understanding a few details about S3 buckets — along with some red flags to look out for when users inevitably make them public — can go a long way towards keeping your org safe.

Why do Amazon S3 buckets often wind up public?

The short answer? Confusing naming and well-meaning users.

Let’s tackle the tricky naming convention first. S3 buckets become public when any permissions are granted to the predefined groups “AuthenticatedUsers” or “AllUsers.” The “AuthenticatedUsers” group represents all AWS accounts, meaning anyone with an AWS account can access that S3 bucket. The “AllUsers” group consists of anyone in the world — and ya can’t get much more public than that.

It’s easy to see how this can cause confusion — especially if you’re new to cloud. Developers and IT admins have grown up in an (on premise) world where groups with “users” in the name are limited to only the employees in their organization. So when Joe over in IT accidentally gives “AllUsers” access to the company directory and unwittingly exposes it to anyone with an internet connection, it doesn’t mean he’s a dummy.

Well-meaning users is another common way that data stored in S3 buckets becomes public. For example, think about an engineer who’s trying to test something and assigns a bucket to “AuthenticatedUsers” so her new teammate can get quick access to it … but then forgets to change the settings back. Or perhaps a team member was testing different permissions but they were never reverted. Or maybe the bucket was never configured properly in the first place.

You get the idea. There are lots of ways that S3 buckets can become public.

How to detect, investigate and respond to Amazon S3 alerts

We see a lot of our customers forwarding their AWS logs to a SIEM, which is what we use to query and spot Amazon S3 bucket misconfigurations. This isn’t the only approach but if you’re interested here’s an explanation to get started using Sumo. Alternatively you can use Amazon Elasticsearch Service to implement alerting, and there are other options as well. Once set up, you can search for AWS “events” which contain indicators that an S3 bucket was made public. We’ve outlined one approach on how to do this below but as those auto ads say “your mileage may vary.” Depending on your tech and how your logs are stored, some of the terms we use may not be the same but should still give you a good idea of what to look for.

The first step is to query for the “PutBucketAcl” event. This event notes when access control lists (ACL) are used to grant permissions on an existing bucket. Next, you’ll need to narrow your search so it only focuses on buckets that have been made public. You can do this by searching for one or both of the predefined S3 Groups as follows,

“http://acs.amazonaws.com/groups/global/AuthenticatedUsers”

“http://acs.amazonaws.com/groups/global/AllUsers”

From there, you’ll need to sift through to get the necessary info. Below are the fields that’ll give you the most useful information to get started with your investigation along with a sample value.

“userName”: “liza”

“sourceIPAddress”: “xx.xx.xx.xx”

“bucketName”: “fix-it-dear-henry”

“URI”: “http://acs.amazonaws.com/groups/global/AllUsers”

“Permission”: “WRITE_ACP”

Now you’ve got all the important investigative leads you’ll need to get started. Based on the information you’ve pulled from the logs, you’ll know the following:

- The user performing the action

- The source of the activity

- The bucket that’s being made public

- The group (such as “AllUsers”) that was granted access

- The permissions that were set for that bucket.

Four red flags we look for when we investigate S3 alerts

Now that you’ve got the data, you’re probably wondering what type of user behavior can tip you off when something fishy is going on with an S3 bucket?

Based on our experience investigating Amazon S3 alerts, here are four red flags — big and small — that we watch for at our customers:

1. Suspicious source IP

If the source IP responsible for an ACL change is coming from a network hosting provider for virtual private networks (VPN) such as IPVanish, that’s strange. You’d expect an employee to be configuring their S3 bucket settings from a known ISP, or at the very least a commonly seen VPN IP. An IP that’s located in another country could (depending on your company) raise eyebrows.

2. Unusual user behavior

A username in your AWS logs (which will look something like “userName”: “Henry.Liza@Corp[.]com” or “arn:aws:iam::XXXXXXXXXXXX:user/Henry.Liza@Corp[.]com”) will help you identify who in your org is making these changes. If the user is in development operations, production support or another administrative role then maybe it’s okay that they’re making configuration changes … but it’s definitely worth checking.

Alternatively, maybe their role doesn’t fit into one of the categories I described above. In that case, you’ll want to figure out why and how the user has these rights. Go search that user’s past activity. Timelining their recent activity can provide a lot of useful information and context.

3. Interesting bucket names

People usually name S3 buckets based on the types of information they put in them. So one way to figure out if an S3 bucket might have sensitive information is to simply look at its name. For example, one S3 bucket we recently investigated had “kops state” in the name and the permission level was set to “READ.” (If you’re not familiar, a quick Google search would reveal that “kops” is a tool used to configure Kubernetes clusters.) The “state” refers to the information needed to manage those clusters, such as configurations and the keys the org is using to do so. That’s not something you want the general public to be able to access!

4. Unnecessary user permissions granted

S3 buckets will have one of five permission types. Three of these are particularly noteworthy: “READ”, “WRITE” and “FULL_CONTROL.” The “FULL_CONTROL” permission level gives users the abilities associated with the other four permissions, such as to list the objects in the bucket (READ), to edit any object in the bucket (WRITE) and more. The permission(s) granted, coupled with the bucket name, will help you gauge the severity and risk.

Amazon S3-related Expel alerts in real life: a quick case study

Here at Expel, we recently detected an S3 bucket at one of our customers that was open to the public. Here’s what the investigation looked like …

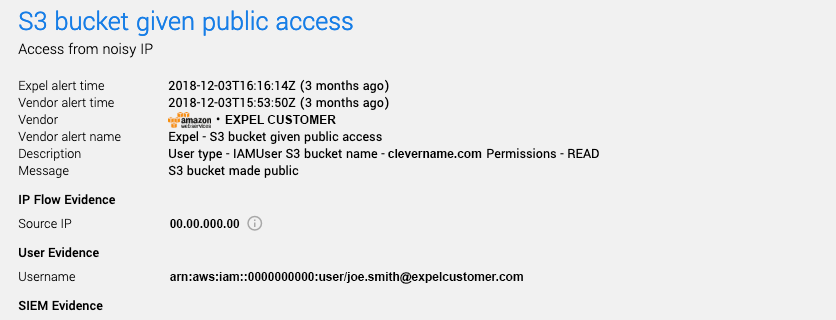

It started with an alert in the Expel Workbench that looked like this:

You can see that the Expel Workbench has already parsed out “Source IP” and “Username” (two of the four red flags we identified above). In addition you can see that when this user made the S3 bucket “clevername[.]com” public, they set the permission level to “READ.” At first glance this seems pretty benign. Wouldn’t you want an S3 bucket that appears to hold a website (based on the name, that is) to be public?

We collect a lot of context from our customers to help us prioritize the severity of alerts. In this case, we were able to use that context to quickly identify the source IP. It was from the customer’s known public address space. If we didn’t have this context, we could have searched for the IP to see if it was used anywhere else in the customer’s environment.

Next, we queried for the user’s recent activity. It turns out that earlier that day, this user had created an S3 bucket with the event “CreateBucket.” We also saw that the user issued other commands such as “GetBucketWebsite,” “PutBucketWebsite”, “GetBucketAcl” and others. The evidence pointed to legitimate user activity — someone was trying to host a website using S3 buckets and test the access controls.

Scanning through the logs, it looked like the user was checking and configuring the bucket’s access controls and policies through commands like “GetBucketPolicyStatus” and “PutBucketAcl.”

We found that the user ultimately deleted the bucket. And by using some open source intelligence (OSINT) — also known as LinkedIn and Google — we discovered that the user worked in a DevOps role for the customer and that the name of the bucket he made public matched the name of an annual charitable event that our customer was hosting. A new IP was stood up that same day with a similar name, which pointed to that bucket. Based on this intel, we concluded that the user was preparing for the launch of this charitable event, possibly testing for the anticipated influx of new website traffic that the customer usually gets around the time of year that they host this benefit.

After digging deeper, we safely closed this investigation without having to notify the customer. The public S3 bucket in question was deleted, and the user’s activity was related to legitimate web hosting purposes.

How to put a lid on your Amazon S3 buckets

If you’re using AWS, keeping an eye out for warning signs that a bucket may have “gone public” should be top of mind. Here are a few pro tips you can implement relatively easily:

- Create a query in your SIEM (or other tech you may be using) to start surfacing alerts when S3 buckets are made public. You can use the fields I shared earlier or terms from Amazon’s documentation to create your own query. By the way, this Access Control List (ACL) Overview page on the AWS website provides a good overview of what ACLs are, how you should (and shouldn’t) use them and how you can keep an eye out for employees making changes to bucket permissions.

- Filter the useful information from those logs I mentioned above and check for red flags such as a suspicious IP, unusual user behavior or unexpected permissions changes being made to an S3 bucket.

- If a bucket in your org was left public or if you suspect that it shouldn’t have been changed in the first place, check with your team to make sure it was intentional. It’s easy for someone to experiment with bucket permissions and then forget to change them back, or leave the bucket public for a little too long.

- If you’ve got a policy that says you shouldn’t have any public S3 buckets, try using AWS Config to monitor them and make sure employees aren’t accidentally making permissions changes.

Want some help keeping an eye on your cloud security? Check in with your MSSP or your SOC to make sure you’re covered.

Don’t have either of those? Let’s talk — we’d love to help.